It is extremely important that before you travel too far down the design or house selection path, you do some NatHERS (Nationwide House Energy Rating Scheme) software modelling. I’ve mentioned it in passing but let’s take a more detailed look at this.

You have probably heard of ‘6-star’ or ‘7-star’ house designs – and how 7-star designs are now largely mandated across Australia. These star ratings are determined by a NatHERS software tool that models the thermal performance of the house design.

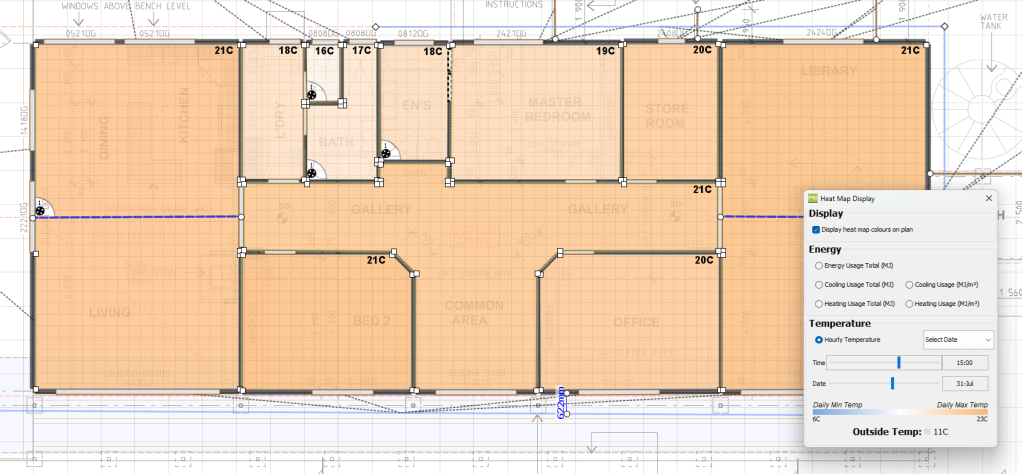

The software tool takes into account the house location and its physical design features – orientation, insulation, thermal mass, window types and locations… almost everything. Many people get NatHERS modelling done to just show the relevant authority that the proposed house meets the minimum energy requirements but doing only this is an absolute waste of what is an amazing design tool.

Wondering if it is worth going from R2.5 to R2.7 wall insulation? Just model the change and find out! Have a splendid view to the west and would like to orientate the house, say, 40 degrees west of north to take advantage of it? OK, use the software to find out what that will do to the thermal performance of the house when compared to a direct north orientation. Wondering if it’s worth the expense of using some interior brick walls to increase thermal mass? Is double glazing worthwhile? Low E glass?

A few key clicks later and you’ll have a good idea. If all this sounds almost too good to be true, take it from me that it isn’t.

You can access the software in two different ways: learn how to drive one of the packages yourself (free software is available) or pay someone else to do it. But to properly use the software, you really need to do a training course – there are many easy traps to fall into, and the software is quite complex to use. (I became so entranced with its capabilities that I did a course in how to use FirstRate5, one of the NatHERS packages that is also free.) However, unless you intend going on to professionally use this skill in the future, I wouldn’t suggest that you take this approach.

Instead, I’d suggest that you approach a NatHERS energy rater, making it clear that you want to trial many changes to the proposed house design. To emphasise that, 99 percent of the work that energy raters do is to try to get house designs past the minimum standard, so what you’re asking them to do is not their normal job. Further, at this stage you wish to model only the performance of the thermal shell – not the ‘whole of home’ (that includes appliances, etc).

To have the house design modelled at even an early stage, you will need to have available at least the:

• Floor, roof, walls and ceiling construction materials and insulation R values.

• Interior layout, including dimensions and room uses (can be a simple sketch to scale).

• Orientation.

• Window and door locations, sizes and types (e.g. the window specifications from the Windows Energy Rating Scheme).

• Eave or veranda overhangs and heights.

That might sound an overwhelming list, but you can easily see that accurate modelling will be impossible without this level of data.

When doing initial modelling, start with major changes – what is the improvement in energy efficiency by using reverse brick veneer versus weatherboard? By having double glazing versus single? By using a timber floor versus a concrete slab? By greatly changing window area on north, east, west or south orientations? By adding a deep veranda on the north?

At this stage you are looking for just the overall star rating. (This rating is quite smart as it takes into account not only the climate but also how the rooms are being used. Furthermore, it assumes that the occupants behave sensibly, like opening windows when that would cool a hot house, etc.)

Some specific design changes will make a dramatic difference to the modelled star rating; others will make much less difference than you might have expected. If you follow the guidelines that have so far been covered in this book, you are very likely to immediately have a good star rating. From there, further improvement often becomes a case of ‘how much do you want to spend?’ – the law of diminishing returns quickly becomes apparent!

Note that in the overall cost of the house, the fees of the software modeller will be quite trivial. Given that a single design decision may cost tens of thousands of dollars (e.g. deciding on the best type of windows), do as many software-modelled design iterations as you can. When you get to the point that more changes means either a reduced star rating, or you’re eking out only tiny gains, it’s probably time to stop.

Leave a comment