The most common way of assessing thermal comfort is to measure inside air temperature. If the temperature is, for example, 22°C, we might think the interior of the house is at a comfortable temperature.

However, it doesn’t take much thought to realise that this might not be so. For example, will that 22°C be comfortable if we are wearing few clothes? Or we’re positioned in a draft? And what are the occupants doing? Are they sitting in a chair reading, or are they working-out on an exercise bike? That 22°C might then be too cold – or too warm.

Furthermore, what is the temperature outside? If it is 38°C outside and we come inside to 22°C, the interior of the house will feel icy! On the other hand, if it is 12°C outside, 20°C inside will likely feel very nice. 8°C outside and 25°C inside? – most Australians would feel that it’s much too hot when they entered the house.

So the first point to consider is that rather than looking at a room temperature as an absolute arbiter of whether the interior is comfortable (neither too hot or too cold), we need to consider the people inside the house: what they’re wearing, what they’re doing and what they’re used to.

People’s perceptions of a comfortable temperature also depend on the climate and season. In summer, an inside temperature of 25°C can be perceived as comfortable, while in winter, 18°C can also be comfortable! Furthermore, for people used to a hot climate, at 20°C inside they’ll be putting on more clothes, while for people living in a cold climate, at 20°C they’ll be removing clothing.

When we moved to the much colder Canberra climate from Queensland, we were amazed to see children heading off to school wearing shorts. After all, it was only 5°C outside! Shorts?! But within a year, our young son was doing the same – he no longer perceived the same temperature in the same way.

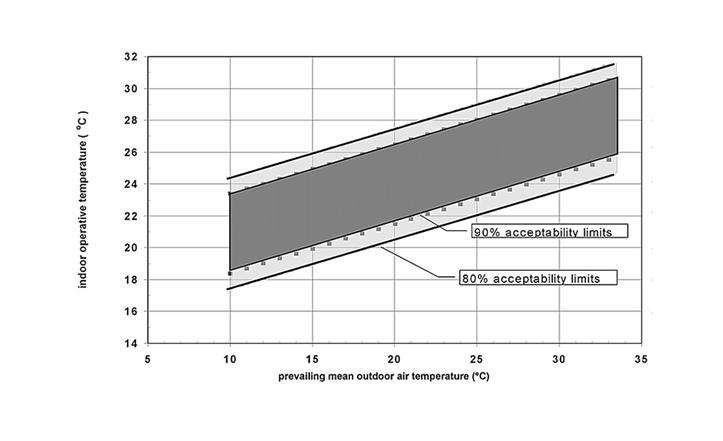

This adaptation to local conditions can be expressed in terms of ‘adaptive comfort’ levels, based on the mean outdoor temperature. The diagram above shows the relationship between comfort, indoor temperature and mean outdoor temperature. (Credit: ASHRAE)

Travelling in northern Europe in winter, to us many hotel rooms felt stifling hot and stuffy. Stifling hot, because we had to take off much of our winter clothing as soon as we came indoors, and stuffy because we couldn’t throw open a window as we were used to doing in the mild climates of Australia. So perception of comfort also has a cultural aspect.

Finally, the temperature at which someone feels comfortable also depends on the individual. I don’t mind warm temperatures in summer. If I am sitting at my desk working in light clothing, I am quite comfortable if there is a ceiling fan rotating and the air temperature is 30°C. However, my wife Georgina in those same conditions would be hot.

So what to make of this? A key point is that a house can be comfortable with a greater range of air temperatures than many people first assume. For two reasons, I think that is an excellent thing.

First, it reduces the amount of energy that needs to be consumed to heat and cool the house.

Second, I think that a natural variation in temperature with the outside environment is to be welcomed. One reason that people often dislike office and commercial spaces is the isolation that the heating and cooling systems give from the natural environment. There are no natural cool breezes in summer, nor variations in temperature during the day. I am not suggesting that the interior house climate should mimic the outside climate, but I do think that the function of a house is to remove the extremes, and not to give constant (or near constant) internal temperatures.

So the temperature at which a given person feels comfortable depends on a myriad of factors – what they’re used to, what they’re wearing, what they’re doing, and their personal preference. When assessing comfort, be wary of looking at temperature alone.

Leave a comment